Photo by Max Langelott on Unsplash

Note: The essay archived below was first published on the book-lovers’ website ShelfPleasure.com in 2012. The site is no longer active. I’m sharing it here as a writing sample.

If you were to look at my nightstand, my coffee table, and my Goodreads profile, you’d see about 400 books. About 390 of them came into my life through the usual means like recommendations and reviews. The rest found me through synchronicity, and those are the ones that I love the most, that I find myself buying, keeping, loaning out, and recommending to others.

Over the years, I’ve read endless articles about how people find books, but never a single one describing how books find people. This, I think, is a critical oversight, because the best books, the ones that make the biggest impact on us, don’t come to us through active seeking; they float into our lives at just the right time, the way a perfect wave will come to a surfer exactly when she’s ready to ride it.

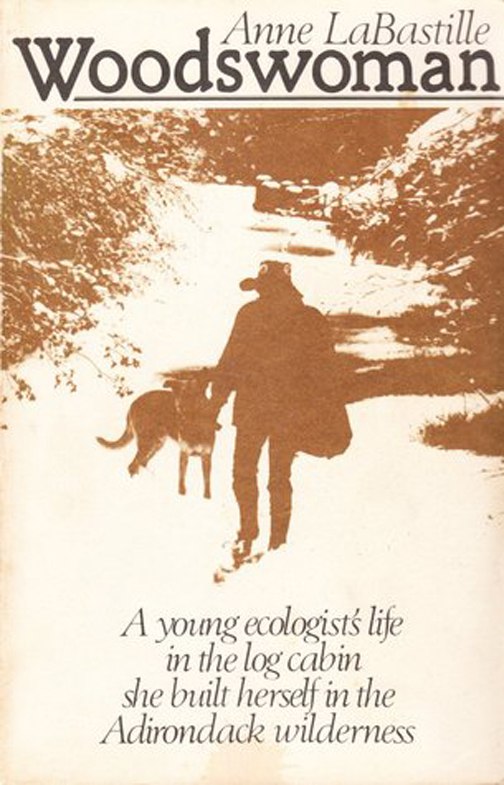

My most recent serendipitous find was Woodswoman by Ann LaBastille. In true “meant-to-be” fashion, I didn’t stumble upon the book itself; rather, I found a newspaper obituary from the Los Angeles Times, taped to the end of a shelf in my favorite used bookstore. The obit was dated 2011 and featured a photograph of a gray-haired woman sitting in a canoe with her German shepherd. After a divorce in the 1970s, it said, LaBastille retreated to the Adirondacks of New York State, built herself a 12 x 12 foot log cabin on the undeveloped side of a remote lake, and remained there for decades, supporting herself as a conservationist consultant, writer, and photographer. In those many years, she’d written several well-regarded memoirs about her life in the woods.

I’m a sucker for naturalist memoirs, and LaBastille’s story in particular resonated with me. I’m not divorced and I have no immediate plans to live off the grid, but I’ve been fascinated with the Adirondacks since attending a summer camp there for a week when I was 16. Saranac Lake, New York was where I discovered my love of the forest, along with a fact about myself that I never knew–that I could, in theory, live my entire lifespan in a canoe or kayak and be perfectly happy.

LaBastille, smiling in her boat, reminded me of why I fell in love with the mountains and lakes of Upstate New York–that sense of freedom and possibility, along with the confidence boost of uncovering an unknown talent. I needed to feel that confidence and independence again.

I wrote her name on my hand and ordered her first memoir, Woodswoman, from the library the next day. When it finally arrived, I tore through it in a few days, enjoying every word. LaBastille had no fear; she trekked into the woods on her own, floated logs across her lake to build her home on her own, chopped down trees on her own. Her life contained no compromise. Because her costs were low, she could take and refuse work based on how much it interested her. The rest of the time, she wrote nature articles and memoirs about the world around her. When she wasn’t writing, reading, or entertaining visitors, she was out exploring the woods and rivers with her dog. She was basically living out my personal mission statement, one I fail to fulfill on a daily basis because striking out on my own is so outside my comfort zone. LaBastille’s adventures made me feel foolish for prioritizing my cowardice. This was a woman who opened her memoir with a description of knocking snow off her boat, literally racing the formation of ice so she could cross the lake and return home to her cabin. Surely I could find it in me to take a few more risks.

In her chapter “Survival,” she wrote a paragraph that spoke to me and my fear:

The first thing was to convince myself that I could handle anything I had or wanted to. The time-old excuse of being a woman, hence frail, dumb, afraid, in need of protection and a man’s assistance, has no place in an isolated and rustic life-style. I believe a woman can do whatever she sets her mind to, once she’s learned how.

Of course, I thought. I can do anything.

Woodswoman drifted into my consciousness at a time when I really needed to hear that message; the right book for the right person at the perfect time. Is it one of the best books I’ve ever read? No. It may not even be the best post-breakup hippie memoir. Wild is more personal, Eat, Pray, Love is funnier and more polished, and Pam Houston’s semi-autobiographical, outdoorsy fiction is more introspective and has better pacing. But those other books are everybody’s. Woodswoman, and the way it slipped into my life like a hypnotic suggestion, feels like it’s mine. What I cherish most about it is not how it’s written or what it’s about, but how it came into my life, and when. One could almost call it fate.

A handful of other fairly obscure books have leaped into my hands while traveling, called to me from late night radio while I’m driving in pajamas in search of fast food, and even eluded me for years, only to show up on a shelf in some faraway shop after I’ve given up all hope of ever finding them.

What each of these books had in common was the feeling that the book and I were meant to end up together. Our stories and back stories matched; my mind was ready; the timing was right. You could almost hear the romantic comedy score rise up behind me when I made the purchase or pulled out the library card.

Maybe I’ve lived in California for too long, but I do believe the most meaningful books, like the most meaningful relationships, come into our lives when we’re ready to receive them. This may be bad news for book marketers, the idea that the fiercest book love is a function of time, residing just outside of their direct influence. But I think it’s wonderful news for literature in general.

If a book is out in the world and has something valuable to say, there will always be someone to find it. I love the idea that if I do someday follow Ann LaBastille’s lead and become a woodswoman, on those rare days that I battle howling snow and ice storms in search of something to read, the one story I most need at that moment will be waiting for me; and something, some force having nothing to do with click-through rates and five-star-Amazon reviews, will guide my hand to find it.